HISTORY OF THE CHATTAHOOCHEE BRICK COMPANY

“There is, or should be, a difference in the life of a prisoner and that of a slave. When persons commit crimes for which they are sent to prison, they forfeit their right to associate with their fellowman, and the policy of the law should be to cut them off from their liberties. It does not contemplate that they should be bound in chains and sold to the one who will pay the most for them; such a system as that is a veritable slavery and should be condemned by all good people.”

— Dr. E. B. Bush, Principal Physician, Georgia Penitentiary

On the eve of the Civil War (1861-1865), the almost four million enslaved African Americans were worth more than all the railroads and manufacturing industries in the United States—roughly 3.5 billion dollars. The enslavement of Africans and their descendants centered capitalism as the United States’ economic and political system of choice and propelled the young nation into a position of leadership in the global market.

By the war’s end, the United States was poised to close its chapter on one of the most brutal and violent eras of crimes against humanity in human history. Yet, even after 600,000+ war dead and the assassination of a president, the states and the federal government were ambivalent about how to codify freedom for the millions of Black women, children, and men who, throughout the country’s history, had been considered property and held in bondage. For many, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was a blessing whose time, finally, had come.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. --13th Amendment, United States Constitution

Passed by the Senate in April 1864, the House of Representatives in January 1865, and ratified by Congress eleven months later, the 13th Amendment (not the Emancipation Proclamation) officially ended the enslavement of Blacks in the United States. The curious condition, “except as a punishment for crime,” paved the way for southern states, primarily, to pass restrictive laws (Black Codes) that thwarted the lives and movement of Black people. Among them were laws that prohibited Blacks from owning weapons, loitering, purchasing property, opening a business, or buying or leasing land. The most insidious laws, perhaps, were vagrancy laws—laws that overwhelmingly criminalized Black men who were unemployed or who engaged in work deemed by Whites to be unacceptable. The amendment’s loophole undermined the abolition of slavery and subjected Black men, women, and children, once again, to the vicissitudes and judicial whims of The State.

Convict leasing, an outgrowth of the Civil War and the new manifestation of Black enslavement, made it possible for local, state, and federal prisons to make money by exploiting the free labor of those locked in their cells. Private businesses, including universities, also benefitted from convict labor. A precursor to the often unjust, inhumane and, sometimes, illegal treatment suffered by incarcerated Blacks (and others) today, the convict lease system accomplished what slavery had since before the country’s founding—harnessing the power of free labor to generate excessive wealth and political and social power.

The Legacy of Convict Leasing

In the years immediately following the ratification of the 13th Amendment, Black men surpassed the number of incarcerated White men. Almost two centuries later, Black men are imprisoned (or impacted by the penal system) at a rate much higher than that of White men. The mass incarceration of Black men is fueled, in part, by the legacy of slavery, conscious and implicit bias against Blacks, and by inequities in criminal legal systems around the country.

Also contributing to the higher-than-average incarceration rate in Black communities is the school-to-prison pipeline—a system borne of zero-tolerance disciplinary policies adopted by numerous school districts that often criminalize the behavior and activities of Black students, boys especially, over the same behavior and activities exhibited by White students.

The Chattahoochee Brick Company project, while grounded in the social, political, and economic histories of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, offers a rare opportunity not only to talk about this history, but also, the project opens numerous avenues for learning and discussion with regards to how this history remains imbedded in our society today—and how we might end it once and for all.

Chattahoochee Brick Company: A Brief History

The Chattahoochee Brick Company was founded by James W. English in 1885. Born in 1837 just outside New Orleans, Louisiana, his parents, Mary and Andrew English, died when he was an adolescent. Following an apprenticeship as a carriage maker (1848-1852), James settled in Griffin, Georgia. He furthered his education with income he made as a carriage maker and began investing in real estate.

A man of his times, English enlisted in the Confederate Army at the onset of the Civil War (April 1861) and served in the 2nd Georgia Infantry Battalion. During his service, English would rise to the rank of captain.

At the close of the Civil War, James English relocated to Atlanta and married Emily Alexander of Griffin, Georgia. They built a home at 40 Cone Street and had three sons and two daughters. His oldest son, J.W. English, Jr. (1867-1914) would serve as vice president of the Chattahoochee Brick Company. His second son, Harry Lee English (1871-1938), would follow his brother as vice president. Harry English Robinson (1914-1995), his grandson, would succeed him as head of Chattahoochee Brick.

In 1877, James English was elected to the Atlanta City Council and in 1881 he was elected to a two-year term as mayor. He served as police commissioner from 1883-1905 and served a brief stint on the board of education. In addition, he was instrumental in convincing voters to move Georgia’s capitol from Milledgeville to Atlanta.

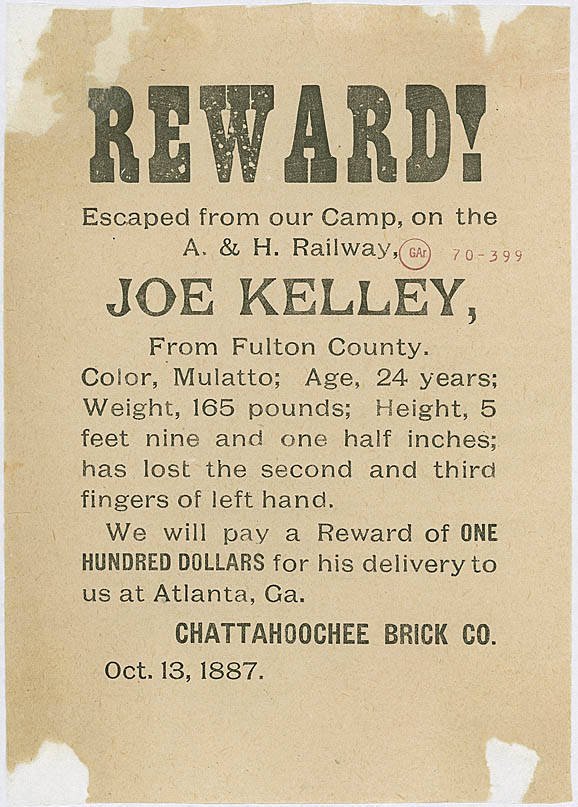

When Georgia established a twenty-year bidding system to manage the state’s convicts, James English was a major investor. In short order, he would buy out one owner, Benjamin G. Lockett, and partner with another, William B. Lowe, to form the Chattahoochee Brick Company on May 7, 1885. At their peak, the other companies produced a maximum of 70,000 bricks per day. Chattahoochee Brick Company would peak at between 200,000 and 300,000 bricks a day.

Each month approximately 175 convict laborers worked at Chattahoochee Brick. They were forced to work in every aspect of brick making and were especially used for the most backbreaking and dangerous work. Convict laborers, in general, were considered expendable and were often whipped and/or worked to death.

From the beginning, the Chattahoochee Brick Company was the source of significant controversy and scrutiny. Numerous site visits by state officials revealed widespread instances of malnourishment, disease, and abuse. Moreover, basic rules (set working hours, keeping the Sabbath, housing, and medical care) often were ignored. Regardless, by 1897, James English and controlled roughly 42% of the convict laborers in the State of Georgia, working them at the Chattahoochee Brick Company and other businesses he owned.

In 1900, fire destroyed many of the buildings on the Chattahoochee Brick Company property. English quickly rebuilt and resumed the company’s high-level production. Across the state, however, the convict leasing system was coming under scrutiny. During the summer of 1908, a Georgia House of Representatives Joint Committee of the Senate and House to Investigate the Convict Lease System of Georgia observed the following at Chattahoochee Brick Company:

We found 178 men at this camp. The men were compelled to work on Sunday and at night. We also found that the convicts were compelled to go in a fast trot, heavily loaded with brick, in loading cars for shipment, even trotting over loose and broken brick. We also found that the convicts were compelled to go into the hot dry kilns, which were likely to kill them. We found the food poor and badly cooked. We found the bedding in a very dirty and unsanitary condition; the floors of the sleeping apartments were also very dirty, and the dining room was unusually filthy and unfit for use for any purpose.

Based on this, and other reports, the Georgia Assembly ended convict leasing on September 20, 1908, effective April 1, 1909. With the end of convict leasing, the Chattahoochee Brick Company switched to a free-labor system. Almost immediately, profits dropped, as more humane conditions had to be instituted. Despite the changes and decrease in production and revenue, the company operated into the 1960s.

In the 1970s, General Shale purchased the Chattahoochee Brick Company site and demolished portions of it (and built newer structures) to accommodate its needs. General Shale operated the facility until 2010, and remaining buildings were demolished the following year.

A Biofuel manufacturer purchased the site in 2016 with the intent of building a fuel distribution terminal but abandoned its efforts due to community opposition and pressure from the City of Atlanta. Acting on behalf of the City, the Conservation Fund negotiated the purchase of the property in 2022.

Return to Chattahoochee Brick and Atlanta Riverlands home page.