Exclusionary policies of the past and present: How single-family zoning structures inequality

By Kendra Taylor, Project Manager, Office of Housing and Community Development

Racial and economic segregation are so prevalent today that it is easy to assume that segregation arises naturally through personal preferences and market forces. However, when examining the origin of many policies today, racial inequality was not just a byproduct of these policies but rather a key feature of them. Patterns of segregation and inequality did not arise unintentionally, but instead represent decades of local, state, and federal policies, shaping who had access to high opportunity neighborhoods and who could build wealth through their homes. One example of such a policy that has shaped inequality in Atlanta is single-family zoning, a land-use policy that restricts any type of housing except for a detached single-family house. Exclusionary single-family zoning has its origins in maintaining racial and economic segregation and today is related to persistent segregation, a lack of diversity in housing, restricting access to high opportunity neighborhoods, and making housing less affordable.

Atlanta City Design

The City adopted The Atlanta City Design in 2017 to envision the way that planning can create a City that is designed for everyone. With resident’s as a central figure, this document outlines the historical context of Atlanta and sets out a vision for a better future. When Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms took office in 2018, she also outlined a vision for making Atlanta a more affordable and equitable city. This included recommending zoning reform to create affordable housing types, and to remedy the historical and contemporary use of zoning for exclusion.

Origins of Single-Family Zoning in Atlanta

Zoning codes are adopted by municipalities to determine the ways that land is used and how residential neighborhoods develop. Zoning can be used to exclude groups, but it can also be used to promote inclusion. Although today zoning cannot be explicitly racist, in cities like Atlanta, zoning codes were once explicitly race-based. When the Supreme Court ruled against explicitly racist zoning policies, zoning codes were redesigned to promote exclusion primarily based on economic status. In this context, single-family zoning emerged to maintain segregation and inequality by creating a zoning category where homes were inaccessible to many.

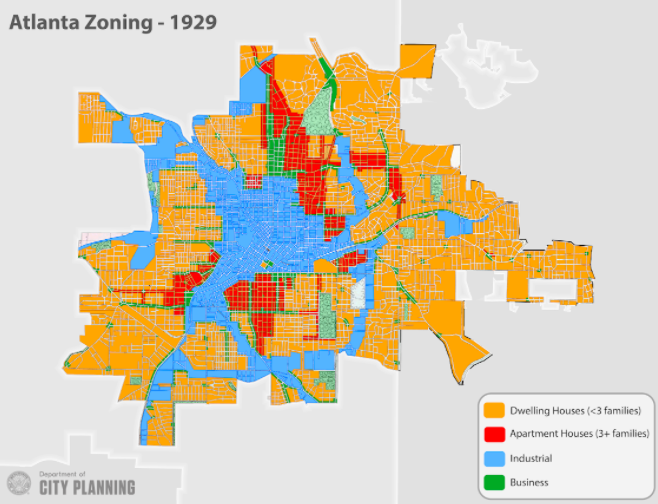

Before it was overturned by a court, Atlanta had an explicitly racist zoning code that classified “White Districts” and “Colored Districts”. To comply with the court ruling, what were “R-1 White Districts” became “Dwelling House Districts” or zones where high-density developments were restricted and “R-2 Colored Districts” became Apartment House districts. Although the zoning code was no longer explicitly race-based, by restricting density the new code in effect made much of the City inaccessible for those that could not afford a detached single-family home. In 1982, when the zoning code was updated to the code still used today, Atlanta’s exclusionary single-family policy was reinforced. Affordable housing types like duplexes, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and basement apartments are not allowed in most of the City which is zoned for single-family. In effect, this limits the ability of low-income residents to live in many areas of the City.

Impacts of Single-Family Zoning

Today, about 60% of Atlanta is zoned for single-family housing. This means that most of Atlanta restricts the availability of housing types which tend to be smaller and more affordable. Additionally, single-family housing restricts the extent to which mixed housing types can exist in close proximity, which means that people from different economic backgrounds have fewer opportunities to share neighborhoods and to share the opportunities that are associated high quality public goods such as quality schools. Single-family zoning does not just deny the opportunity for diverse housing types and economically diverse neighborhoods in effect; it was in fact designed to exclude residents explicitly based on socioeconomic status in response to the invalidation of explicitly race-based zoning.

Like in years past, single-family zoning today is related to several problems that Atlanta faces including: 1) unequal access to high opportunity neighborhoods for low-and-moderate income residents;

2) the increasing cost of housing as zoning limits the supply of both affordable and market-rate housing;

3) economic segregation in housing.

Remedies

What can be done? Cities and states are grappling with how to address discriminatory policies of the past and create more affordable housing options for the present. Atlanta could directly address the exclusionary nature of single-family zoning by allowing an additional unit on all single-family zoned lots. This could permit more affordable options like basement apartments or Accessory Dwelling Units. There are many potential benefits of this type of gentle density. First, changing zoning rules to be inclusionary rather than exclusionary can improve affordability and increase the supply of housing.

By acknowledging the exclusionary roots of single-family zoning and changing it, we can foster economic and housing diversity in neighborhoods that is beneficial to resident of all backgrounds. And changing the zoning code to be more inclusive offers an opportunity for wealth creation. Allowing for development of an additional housing unit on current single-family properties can create both much needed additional housing units for a City in short supply of low-cost housing and create an additional source of income for residents. Arguments in support of single-family zoning that are not explicitly racist or classist often rest on the desire to preserve the character and aesthetics of certain neighborhoods and the preferences for single-family homes as a way of life. However, by introducing the nuanced zoning change of an additional unit, the physical character of a neighborhood can be preserved even while new, and more affordable, housing options are created.

Exclusionary single-family zoning is just one example of a housing policy that has systematically fostered inequality in housing. But its continued use in municipalities across the U.S., including in progressive places like Atlanta, reveals the challenges associated with ending exclusionary zoning. But by preserving single-family zoning, we are continuing a policy that has roots in intentional racial and economic discrimination and has the effects of limiting equitable growth and opportunity today.

To learn more about Atlanta’s policy proposals and research the City has conducted, visit Atlanta City Design Housing here.